Have you ever wondered how complex financial products are broken down into manageable pieces for different types of investors? That’s where tranching comes in. It’s a process used to divide financial products, like loans or securities, into different layers, or “tranches,” each with its own level of risk and reward. Whether you’re looking at mortgage-backed securities, corporate bonds, or even private equity, tranching is the key to making these products more flexible and appealing to a wide range of investors.

In simple terms, it allows investors to pick the level of risk they’re comfortable with while still being part of the same investment pool. This guide will explain what tranching is, how it works, and why it’s such a powerful tool in the world of finance—making it easier to navigate investments, risk, and rewards.

What is Traunch?

A truanch, or tranch, is a slice or portion of a larger financial product, typically used in structured finance to divide risk and return. The term originates from the French word for “slice” and is commonly applied to securities such as mortgage-backed securities (MBS), collateralized debt obligations (CDOs), and other asset-backed securities (ABS). Tranching allows investors to purchase portions of a financial product based on their risk preferences, with each tranche offering different levels of risk and potential return.

For example, in a mortgage-backed security, an issuer may pool together thousands of individual home loans and then divide these loans into different tranches. Each tranche is assigned a certain level of priority when it comes to receiving payments from the underlying mortgages. The senior tranches, which carry lower risk, receive payment first, while subordinated tranches, which are higher-risk, receive payments only after the senior tranches have been paid. This segmentation helps make complex financial products more attractive to a wider range of investors, allowing them to choose the level of risk they are willing to take.

Tranch vs. Traunch

In finance, “tranch” and “traunch” are often used interchangeably, but they technically refer to the same concept. Both terms describe a portion or slice of a larger financial product, typically used in the context of structured finance, such as debt issuance, securitization, or investment funds.

-

Tranch (pronounced “trawnsh”) is the correct term in finance. It originates from the French word tranche, which means “slice” or “portion.”

-

Traunch is a common misspelling or alternative spelling of tranch, though it’s widely used in casual contexts, especially in media and everyday conversations.

Both terms refer to segments of a financial product that are structured to offer different levels of risk, return, or priority for payment. For example, in a collateralized debt obligation (CDO), different tranches may represent different risk levels, with the senior tranches having priority in terms of payment over more junior tranches.

In short, they mean the same thing, but tranch is the correct and more formal term.

Importance of Understanding Tranches in Financial Contexts

Understanding tranches is essential for navigating complex financial products, especially in structured finance. Tranching is used to manage risk, enhance returns, and make investments more accessible to a diverse set of investors. By dividing a product into different tranches, financial institutions can cater to investors with different risk appetites, from those seeking safe, stable returns to those willing to accept more risk for the chance of higher rewards. Additionally, tranching helps allocate risk in a way that can reduce systemic financial exposure and improve market liquidity.

- Improved risk management: Tranching allows investors to balance their exposure to risk by selecting tranches that align with their individual investment goals.

- Increased market accessibility: By creating multiple tranches with varying risk levels, tranching makes complex financial products more accessible to a broader range of investors.

- Enhanced liquidity: Tranching helps increase the tradability of financial products, as investors can buy or sell tranches with different risk profiles based on their needs.

- Better investment decision-making: Understanding tranching allows investors to make informed decisions about their investment strategy by clearly identifying the risk and return profile of each tranche.

- Facilitates diversification: Tranching helps diversify portfolios by providing access to different layers of risk and return in a single financial product.

Brief History and Evolution of Tranches

The concept of tranching has its roots in the world of structured finance, particularly in the creation of asset-backed securities. The use of tranches gained widespread attention in the 1980s and 1990s as financial institutions began to pool and securitize loans, such as mortgages, to create new investment products. The development of mortgage-backed securities in the United States, followed by the rise of collateralized debt obligations, was a key moment in the evolution of tranching.

Initially, tranching was used primarily for managing the risks associated with mortgage pools, where investors in senior tranches were protected from defaults by the underlying loans. Over time, however, tranching expanded into other areas of structured finance, including the securitization of corporate bonds, auto loans, and even credit card debt. The flexibility of tranching allowed financial products to become more customizable, meeting the demands of a growing investor base with varying risk profiles.

The global financial crisis of 2007-2008 highlighted the risks associated with overly complex tranche structures, especially in subprime mortgage-backed securities. These products were poorly understood by many investors and were subject to significant volatility when the underlying assets failed to perform as expected. This crisis led to increased regulatory scrutiny and changes in how tranches were structured and marketed, but the basic principle of dividing risk into manageable pieces has remained a core part of structured finance.

Today, tranching is widely used not only in traditional asset-backed securities but also in private equity, venture capital, and even in modern blockchain-based financial products. As financial markets continue to evolve, the methods of structuring and distributing risk through tranching will likely adapt to new technologies and market conditions, making it a continuously relevant concept in the world of finance.

The Mechanics of Traunching

Tranching is a fundamental concept in structured finance, often used to divide financial products or securities into multiple layers, each with its own distinct risk and reward profile. The core idea is to create a hierarchy of investment levels, where each tranche receives different levels of return and priority in terms of payment. Let’s break down how tranching works and why it’s so crucial in managing investments.

Tranching works by pooling together assets or debt instruments, such as loans, mortgages, or bonds, and then slicing them into separate pieces. These pieces, known as tranches, can then be sold to investors, each with a different appetite for risk. The highest tranche, usually the senior tranche, is the safest investment because it gets paid first and has a lower chance of losing principal. The lower tranches, such as the subordinated tranches, come with more risk because they are paid only after the senior tranches have been fully satisfied.

How Tranching Works in Financial Transactions

In financial transactions, tranching is used primarily in products like mortgage-backed securities (MBS), collateralized debt obligations (CDOs), or other forms of asset-backed securities. A financial institution may pool together thousands of individual loans or mortgages and then split them into several tranches. Each tranche represents a portion of the risk and rewards tied to the performance of the underlying assets.

For example, consider a CDO that includes various types of loans. The institution will divide this portfolio into traunches based on different levels of risk. The senior tranche might have a high credit rating and receive priority payments. The middle tranche may be a bit riskier, offering a higher return, while the bottom tranche might be a high-risk investment, offering the highest potential returns but with significant risk if the underlying loans default.

The Role of Risk and Reward Distribution

One of the most important aspects of tranching is how it distributes both risk and reward. The entire purpose of tranching is to create a more manageable and attractive investment structure. By dividing the underlying asset pool into layers, tranching allows different types of investors to access the same financial product based on their risk tolerance.

The senior tranches are the least risky because they are the first to receive payments from the underlying asset pool. Investors in these tranches are more likely to get their money back, even if some of the loans or assets default. In return for this lower risk, senior tranche investors usually receive a lower return on their investment.

On the other hand, subordinated tranches bear more risk because they are the last to receive payment. If the assets in the pool perform poorly or defaults occur, investors in the lower tranches may not receive any payments. However, to compensate for this higher risk, these tranches typically offer higher returns. This risk-reward tradeoff is what makes tranching so appealing to a diverse range of investors.

Key Components Involved in the Traunching Process

Several key components are involved in the process of tranching, and understanding them can help clarify how tranching works in practice. The most important elements include the asset pool, the payment waterfall, and the credit enhancement structures.

The asset pool refers to the underlying financial products that are pooled together to create the security. For example, in mortgage-backed securities, the asset pool is made up of individual home loans. In CDOs, the pool might consist of different kinds of debt, such as corporate bonds, mortgages, or loans.

The payment waterfall is the order in which investors in each traunch are paid. The senior tranches are the first to receive payments, followed by the mezzanine tranches, and finally the equity or subordinated tranches. This hierarchy is crucial because it ensures that the highest priority tranches are paid first, minimizing the risk for those investors.

Lastly, credit enhancements are used to make tranches more attractive to investors. These enhancements can include over-collateralization (where the value of the underlying assets exceeds the amount issued in securities), insurance, or third-party guarantees. These tools help reduce the perceived risk of lower tranches, allowing institutions to attract a wider pool of investors.

Tranching is a strategy that allows investors to select from a range of securities that meet their risk profiles. By structuring investments this way, financial institutions can offer a product that appeals to both conservative investors, looking for stable returns, and risk-seeking investors, willing to take on more risk for the potential of higher rewards.

Common Uses of Traunching

Tranching is a versatile tool that is applied in various areas of finance, helping to structure investments in a way that matches different investor needs and risk profiles. This method is often seen in structured finance products, loan and mortgage-backed securities, investment funds, and complex financial instruments like CDOs. Let’s explore how tranching is used in these areas and why it is such an integral part of modern finance.

Structured Finance and Securities

Structured finance refers to the creation of complex financial products that are designed to redistribute risk and tailor investments to specific market demands. Tranching plays a central role in this process, particularly in the creation of asset-backed securities (ABS), which are financial instruments backed by a pool of assets like loans, receivables, or mortgages. By dividing these securities into tranches, institutions can appeal to a wide range of investors, each with a different risk appetite.

Structured finance products can involve multiple layers of tranches, where each layer has a distinct risk and return profile. For example, in an ABS, senior tranches offer lower risk and return, while subordinated tranches provide higher returns in exchange for greater risk. This segmentation helps create a more diverse investor base, as it allows those who seek lower-risk, stable returns to invest in the senior tranches, while those who are willing to take on more risk for higher returns can invest in the lower tranches.

Traunching in structured finance also enhances the liquidity of these securities. By dividing the product into multiple tranches, it is easier for the securities to be bought and sold in the market, as each traunch appeals to different investor types. This increases market efficiency and provides greater flexibility to both issuers and investors.

Loan and Mortgage-Backed Securities

One of the most well-known applications of tranching is in the creation of loan and mortgage-backed securities (MBS). MBS are created by pooling together individual loans or mortgages, which are then divided into tranches and sold to investors. The tranches in MBS are structured so that different types of investors can buy into the securities based on their risk tolerance.

The senior tranches in an MBS are typically backed by the safest, most stable mortgages, which are less likely to default. These senior investors receive payments first and have a lower risk of losing money. Conversely, the subordinated tranches are composed of higher-risk mortgages, which may include loans to borrowers with less favorable credit profiles. These tranches provide higher returns to compensate for the increased likelihood of defaults.

By structuring MBS in this way, financial institutions can attract a broad spectrum of investors, from those looking for low-risk, stable returns to those willing to take on more risk for the chance of higher yields. The creation of tranches allows the underlying mortgage pool to be sliced into pieces that can suit different investment strategies, whether conservative or aggressive.

For example, an MBS backed by prime mortgages (loans to borrowers with high credit scores) may offer a lower return and be split into several senior tranches, while an MBS backed by subprime mortgages (loans to borrowers with lower credit scores) may offer a higher return but with more risk, and thus have subordinated tranches that bear the brunt of any defaults.

Investment Funds and Private Equity

Tranching is also widely used in the context of investment funds and private equity. In private equity, investors typically pool capital to invest in a variety of businesses or assets. Tranching allows these investments to be structured so that different investors can take on varying levels of risk and potential reward, depending on their investment goals.

For example, in a private equity fund, the capital might be divided into tranches based on the stage of the investment. Early investors, who are taking on more risk, may be allocated subordinated tranches with higher potential returns, while later-stage investors might invest in senior tranches, which offer more stability but with lower returns. These different tranches provide investors with the flexibility to tailor their investments according to their risk tolerance and the nature of the underlying investment.

In the case of investment funds, tranching allows fund managers to create products that appeal to both risk-averse investors seeking consistent returns and those willing to accept volatility for potentially higher returns. The structure of tranches enables funds to meet the diverse needs of their investor base, whether they are looking for security or higher growth.

Private equity deals, in particular, benefit from tranching as it enables more sophisticated capital structures that can be used to allocate financial risk and return in a way that aligns with the interests of both the fund and the investors. It also provides flexibility in terms of deal structuring, allowing for the creation of multiple layers of investment that suit different market conditions and investor requirements.

Securitization and Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDOs)

Securitization is the process of converting illiquid assets into tradeable securities. Tranching is at the heart of this process, as it enables the creation of securities from asset pools like mortgages, loans, and bonds. The tranches created from these pools offer investors a way to invest in different segments of the overall asset pool, each with varying levels of risk and return.

A common example of securitization is the creation of collateralized debt obligations (CDOs), which are structured products made up of a pool of loans, bonds, or other debt instruments. These products are divided into tranches based on credit quality and risk. The senior tranches are the first to be paid and typically offer lower returns, while the subordinated or equity tranches take on the most risk but also offer the potential for higher returns.

CDOs play a significant role in the financial markets by providing an avenue for investors to gain exposure to different types of debt, while also allowing institutions to distribute and manage the risks associated with these assets. By dividing the debt pool into tranches, CDOs create investment opportunities for a wide range of investors, from those seeking secure, low-risk returns to those willing to accept higher risks for greater rewards.

Tranching in CDOs also facilitates the management of default risk. If the underlying assets in the pool experience defaults, the lower tranches are the first to absorb the losses, protecting the senior tranches from significant damage. This structure helps mitigate the overall risk for the investors in higher tranches while still allowing those in lower tranches to potentially earn substantial returns if the assets perform well.

In essence, tranching in securitization and CDOs allows for the redistribution of risk in a way that benefits both issuers and investors. It enables institutions to offer complex, customizable products that can appeal to a wide array of investors, while also enhancing liquidity and providing flexibility in managing and mitigating risk.

Types of Tranches

When financial products like mortgage-backed securities or collateralized debt obligations are created, they are often divided into different layers called “tranches.” Each tranche has its own risk profile, priority for payment, and potential return. These distinctions help meet the diverse needs of investors by offering varying levels of risk and reward. Let’s explore the most common types of tranches and how they function in structured finance.

Senior Tranches vs. Subordinated Tranches

The most fundamental distinction in tranching is between senior tranches and subordinated tranches. These two types of tranches are structured differently to appeal to investors with different risk appetites.

Senior tranches are the highest-ranking layers in a structured financial product. These tranches receive the first payments from the underlying asset pool, making them the safest investment. Since they have priority over other tranches, they are considered low risk but offer lower returns. For example, in a mortgage-backed security (MBS), senior tranches would be the first to be paid if some of the underlying mortgages default. Because these tranches have priority, they are often rated highly by credit rating agencies and are more attractive to conservative investors.

On the flip side, subordinated tranches are the lowest-ranking layers and are the last to receive payments. These tranches bear the most risk because, in the event of defaults or poor performance from the underlying assets, they are the first to absorb any losses. However, to compensate for this higher risk, subordinated tranches offer higher returns. Investors willing to accept the risk of receiving their payments last, or possibly not at all in a worst-case scenario, are attracted to these tranches. They may provide significant rewards if the asset pool performs well, but they come with the potential for major losses if things go wrong.

This structure—where senior tranches get paid first, followed by subordinated tranches—creates a hierarchy that aligns with different investor preferences, balancing security and yield in a way that is suitable for a broad range of market participants.

Investment-Grade Tranches

Investment-grade tranches are typically considered safer investments because they are backed by assets that have a lower likelihood of default. These tranches are often composed of high-quality, low-risk loans or bonds, such as prime mortgages or highly-rated corporate bonds. Investment-grade tranches are rated highly by credit rating agencies (typically AAA, AA, or A), meaning they have a very low risk of losing principal.

The security of investment-grade tranches lies in the fact that they are typically senior tranches or highly secured by collateral. Because these tranches receive payment before the subordinated ones, and because they’re backed by less risky assets, they are ideal for conservative investors who are looking for steady, predictable returns without exposure to significant volatility.

While the returns on investment-grade tranches are generally lower compared to riskier tranches, their appeal lies in their stability. These tranches are perfect for institutional investors, such as pension funds or insurance companies, that have strict risk management requirements and prefer low-risk, steady investments. Investment-grade tranches play a key role in making structured finance products attractive to a broad spectrum of investors, including those with low risk tolerance.

Risk-Based Traunches (High-Risk, Low-Risk)

Tranching also allows for the creation of risk-based tranches, which are structured to cater to different levels of investor risk appetite. These tranches are organized based on the level of risk they carry and the potential returns they offer.

- High-risk tranches are typically the most subordinated layers in a structure. These tranches are the last to be paid and are the most vulnerable to losses in the event of defaults. However, they offer the highest potential returns, making them appealing to investors who are willing to take on more risk for the possibility of significant rewards. These tranches might be composed of loans or bonds that are considered higher risk, such as subprime mortgages or junk bonds.

- Low-risk tranches are generally composed of assets with lower credit risk. These traunches are typically higher up in the structure, meaning they are paid before the higher-risk tranches. The lower risk associated with these tranches leads to lower returns, but they offer greater security, making them attractive to more conservative investors. These tranches might consist of prime mortgages, investment-grade corporate debt, or other low-risk assets.

The division between high-risk and low-risk tranches allows investors to choose a level of exposure that fits their goals. Those seeking higher returns can opt for the higher-risk tranches, while those prioritizing safety can invest in the low-risk tranches. The flexibility that tranching offers in terms of risk-based categorization is one of its most attractive features, as it provides investors with tailored options for different financial strategies.

Waterfall Structures and Their Impact

The waterfall structure is a critical concept in tranching because it determines the order in which payments are made to the different tranches. The term “waterfall” describes the flow of payments from the top down, with each tranche receiving payments based on its priority.

In a typical waterfall structure, the senior tranches are paid first, and once they are fully satisfied, any remaining funds flow down to the next tranche in line. This payment hierarchy ensures that those who bear the least risk—typically the senior tranches—are compensated first. The lower tranches only receive payments once all higher-priority tranches have been paid in full.

The impact of the waterfall structure is profound because it shapes the risk and return profiles of each tranche. Senior tranches, being paid first, have a higher degree of certainty and lower risk, while subordinated tranches, which are paid last, face more uncertainty and thus carry higher risk and the potential for higher returns. The waterfall structure also impacts the pricing of each tranche: senior tranches typically offer lower returns because they are seen as safer investments, while subordinated tranches offer higher returns as compensation for their higher level of risk.

Understanding the waterfall structure is crucial for investors because it helps them determine the likelihood of receiving payments, the timing of those payments, and how the performance of the underlying assets may impact their investment. The flow of payments affects everything from credit ratings to yield expectations, and it plays a key role in the attractiveness and risk level of a particular tranche.

Tranches come in many forms, each designed to meet the needs of different types of investors. Senior tranches offer safety, subordinated tranches provide high returns at higher risk, and investment-grade tranches cater to conservative investors seeking stability. Meanwhile, the waterfall structure governs how funds flow through these layers, directly influencing risk and reward for each tranche. Understanding these various types of tranches and their structures is essential for navigating complex financial products and making informed investment decisions.

Tranching Examples

Tranching is a widely used practice in structured finance, and its impact can be seen across various real-world financial products. By breaking down large, complex assets into manageable portions, tranching helps investors better understand risk and reward while allowing institutions to create products that can appeal to a broad range of investor profiles. Let’s explore some real-life examples to see how tranching is used in different financial markets.

Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS)

Mortgage-backed securities are perhaps the most well-known example of tranching in action. In an MBS, banks or other financial institutions pool together a large number of home loans or mortgages and then divide this pool into various traunches. These tranches are ranked by risk, with the senior tranches receiving payments first and the subordinated tranches receiving payments only after the senior tranches have been fully paid.

For example, in a typical MBS structure, the senior tranches might be composed of prime mortgages—those with low default risk—while the subordinated tranches could include subprime mortgages, which are more likely to default. In this structure, senior traunch investors receive their payments first, giving them a safer, more stable return, while subordinated tranche investors face greater risk but have the potential for higher returns if the mortgages perform well.

During the 2008 financial crisis, many MBS products were heavily affected due to defaults in subprime mortgages. However, the tranching structure helped mitigate risk for senior tranche investors who were less impacted by the defaults. On the other hand, the subordinated tranches experienced significant losses, highlighting both the advantages and the risks of the tranching process.

Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDOs)

Collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) are another example of how tranching is applied in finance. CDOs are structured financial products that pool together various debt instruments, such as corporate bonds, loans, or mortgage-backed securities. These debt instruments are then divided into tranches, each with different risk levels. The senior tranches receive priority for payment, while the subordinated tranches are paid last and are more vulnerable to defaults.

In a typical CDO structure, investors in senior tranches are paid first, as long as the underlying debt in the CDO performs well. If the debt instruments in the CDO pool perform poorly or defaults occur, the subordinated tranches are the first to bear the losses. Investors in these junior tranches can potentially earn higher returns if the underlying debt performs well, but they are also exposed to the greatest risk if defaults occur.

The collapse of the CDO market during the 2008 financial crisis is one of the most dramatic examples of how tranching can amplify risk. Many CDOs were made up of subprime mortgages, which ultimately led to massive defaults. While senior tranche investors were protected to some extent, those in the subordinated tranches experienced substantial losses, showcasing how the structure of tranching can lead to significant exposure when the underlying assets underperform.

Asset-Backed Securities (ABS)

Asset-backed securities (ABS) are similar to mortgage-backed securities but are backed by other types of loans, such as car loans, student loans, or credit card debt. Like MBS, ABS are divided into tranches that cater to different investor risk profiles. The senior tranches are backed by safer, more predictable loans, while the subordinated tranches are backed by riskier loans, offering higher potential returns for investors willing to take on more risk.

For example, in a car loan ABS, the senior tranches might be composed of loans made to borrowers with strong credit histories, while the subordinated tranches could consist of loans made to borrowers with weaker credit. The senior tranches are more likely to receive their full payment if the underlying loans perform well, while the subordinated tranches may face losses if defaults occur. This makes ABS a flexible product for investors who want exposure to consumer credit without having to buy individual loans.

ABS have become particularly popular in recent years as the market for consumer debt has expanded. By pooling together different types of loans and tranching them, financial institutions can create products that appeal to investors with different risk appetites, from conservative investors looking for low-risk returns to more aggressive investors seeking higher yields.

Private Equity and Venture Capital

Tranching is not limited to traditional asset-backed securities or debt instruments—it is also widely used in private equity and venture capital (VC) deals. In these types of investments, funds are often raised in stages or tranches, with different investor groups contributing capital at different points based on the success of previous funding rounds or milestones.

For example, in a venture capital deal, the initial tranche of funding may be provided by angel investors or seed investors who are willing to take on a high level of risk in exchange for the potential for significant returns if the startup succeeds. Later funding rounds may be provided by venture capital firms, which may invest in a subsequent tranche based on the performance and progress of the company. These later-stage investors are often more risk-averse, so their tranche is structured to offer a lower return but a higher degree of protection compared to earlier investors.

This type of tranching in venture capital allows companies to raise capital over time while managing the risk exposure for each investor. It also gives investors the ability to choose a level of risk they are comfortable with, depending on the stage of the investment. The different tranches may also provide different rights or preferences, such as priority for dividends or liquidation proceeds, depending on the terms of the deal.

Structured Investment Vehicles (SIVs)

Structured Investment Vehicles (SIVs) are another example of how tranching is used in the finance world. SIVs are complex financial products that pool together various types of assets, such as mortgages, loans, and other debt instruments. These assets are then divided into tranches, and investors can purchase exposure to these tranches based on their risk preferences.

For example, a SIV may pool together a combination of high-grade corporate bonds, mortgage loans, and lower-grade assets like subprime debt. The senior tranches of the SIV might be composed of high-quality corporate bonds, while the subordinated tranches might consist of lower-quality assets. The senior investors in the SIV receive payments first, but are also subject to lower returns compared to those who invest in the more subordinated, riskier tranches.

SIVs became especially popular in the years leading up to the 2008 financial crisis, as they allowed financial institutions to pool a variety of assets and sell them in a way that appealed to investors with different risk appetites. However, when the housing market collapsed and the value of subprime mortgages fell dramatically, the more subordinated tranches of SIVs faced heavy losses, while senior tranche investors were somewhat insulated. This created significant problems for investors who didn’t fully understand the underlying risks of these complex products.

The Role of Tranching in Risk Management

Risk management is one of the key benefits of tranching, especially in the context of structured finance. Tranching allows financial institutions to tailor investment products in ways that manage and distribute risk effectively across a variety of investors. By dividing a pool of assets into different tranches, each with its own risk profile, financial products can be structured to meet the needs of investors with varying risk tolerances.

Tranching helps distribute risk by allocating different layers of the asset pool to different groups of investors. Each tranche has its own level of exposure to the performance of the underlying assets. Senior tranches, which are the first to receive payments, are protected from losses up to a certain point, while subordinated tranches, which are last in line for payment, carry more risk but also offer higher potential returns. This hierarchy allows the risk to be absorbed by the lower tranches first, protecting those in higher-ranking tranches.

Through this distribution of risk, tranching creates investment products that can appeal to a broader range of investors. Risk-averse investors can focus on the senior tranches, which offer more stability and less exposure to default, while investors with a higher risk tolerance can invest in the more junior tranches, where the returns are higher but the potential for loss is greater.

Benefits of Risk Mitigation Through Tranches

- Risk mitigation and allocation: Tranching effectively distributes risk across various investors, reducing the potential for any one investor to bear too much of the loss.

- Diversification within a single product: By structuring tranches, an investment can provide exposure to multiple levels of risk, offering diversified opportunities within a single financial instrument.

- Increased investor participation: Investors with different risk appetites can select the tranche that fits their goals, making complex financial products more accessible and flexible.

- Improved stability for senior investors: The senior tranches are protected from losses, creating more stable returns for risk-averse investors.

- Potential for higher returns for junior investors: Investors in subordinated tranches are rewarded with higher returns, compensating for the increased risk of default they face.

Impact on Investment Decisions and Strategies

Tranching significantly influences investment decisions and strategies. By offering a range of risk and return profiles, tranching allows investors to carefully select tranches that align with their specific financial goals and risk tolerance. For conservative investors, the availability of low-risk, senior tranches provides a stable option, ensuring that their capital is protected as much as possible. On the other hand, risk-seeking investors may opt for lower tranches, where they can take advantage of potentially higher returns in exchange for accepting greater risk.

For financial institutions, the ability to create these tailored investment opportunities is a key strategic advantage. Tranching allows them to attract a diverse range of investors, from institutional funds seeking steady income to hedge funds looking for higher returns. The flexibility provided by tranching also allows institutions to manage liquidity better and adjust their portfolios according to market conditions.

Moreover, tranching plays a crucial role in managing systemic risk, especially in large-scale financial products like mortgage-backed securities or collateralized debt obligations. By spreading risk across different tranches, it ensures that defaults or losses are absorbed gradually, preventing them from destabilizing the entire financial product. This layered approach not only protects investors but also enhances the overall resilience of the financial market.

Ultimately, the role of tranching in risk management is to offer a way to balance risk and reward. By giving investors a choice of risk levels and providing a mechanism to manage defaults, tranching creates opportunities for a broad range of market participants while minimizing the overall risk exposure. Understanding how tranching impacts investment decisions and strategies is crucial for making informed choices in complex financial products.

Financial Models Involving Tranches

Tranching is integral to many financial models, particularly in structured finance, where it is used to divide complex financial products into simpler, more manageable layers. These models enable financial institutions to create products that cater to different investor needs, offering varying levels of risk and reward. The use of tranches can be seen in various models such as asset-backed securities, collateralized debt obligations (CDOs), and mortgage-backed securities (MBS). By breaking down assets into multiple layers, institutions can better manage risk, improve liquidity, and enhance the appeal of their offerings to a wide range of investors.

Structured finance models that use tranching often revolve around pooling a variety of financial assets, such as mortgages, loans, or bonds, and then dividing these pooled assets into separate tranches. Each tranche has distinct characteristics that determine its risk and return profile, which in turn influences investor behavior and market demand. These models typically involve complex cash flow structures, with the payments from the underlying assets flowing through a series of tranches before reaching the final investor.

Calculating Yields and Returns in Different Tranches

One of the key features of tranching is the ability to offer different yields and returns based on the priority of the tranche in the payment structure. The calculation of yields and returns can vary widely depending on whether an investor is holding a senior or subordinated tranche.

The yield for each tranche is typically determined by several factors, including:

- Priority of payments: Senior tranches receive payments first, and as a result, they tend to offer lower yields. The higher the risk an investor takes on (such as investing in subordinated tranches), the higher the potential return.

- Risk of the underlying assets: Tranches that are backed by higher-risk assets (such as subprime mortgages or high-yield bonds) will generally offer higher returns to compensate investors for the increased risk.

- Market conditions: Interest rates, credit spreads, and the overall economic environment can affect the yield of each tranche. For instance, in a rising interest rate environment, investors might demand higher yields to compensate for inflation risks and the opportunity cost of not investing elsewhere.

Calculating the return for each tranche involves assessing the payment flows through the tranches over time. For example:

- Senior tranches: These tranches often have lower returns due to their lower risk, and the returns are typically stable and predictable, provided the underlying assets do not experience significant defaults. For a senior tranche, an investor might calculate the return based on the fixed or floating interest payments and the likelihood of full payment from the underlying assets.

- Subordinated tranches: In contrast, subordinated tranches offer higher returns, but the risk of loss is greater. The return for a subordinated tranche depends not only on the asset pool’s performance but also on the extent to which defaults affect the tranche’s ability to receive payments.

For example, let’s assume a CDO has three tranches: senior (AAA-rated), mezzanine (BB-rated), and equity (unrated). If the underlying asset pool generates $10 million in revenue, the senior traunch might receive $6 million, the mezzanine tranche $2 million, and the equity tranche $1 million. The senior tranch would receive its payments first, with any leftover revenue flowing to the mezzanine and equity tranches.

Tranche Waterfall Models for Structured Finance

A waterfall model is a critical component of structured finance, as it governs the order in which payments are made to each tranche. The term “waterfall” comes from the cascading flow of payments, where the most senior tranches are paid first, followed by the subordinated tranches. The order of payment is usually predetermined, and it directly impacts how the returns are distributed across different layers.

In a simple waterfall structure:

- Senior tranches are paid first. These tranches typically consist of the safest, least risky assets, such as investment-grade loans or bonds. They are given the highest priority in the payment structure and are typically the first to be paid from the cash flow generated by the asset pool.

- Mezzanine tranches are paid next. These tranches are subordinated to the senior tranches but are paid before the equity or equity-like tranches. Mezzanine tranches are typically higher risk than senior tranches, as they will only receive payments after the senior tranches are fully satisfied.

- Equity or subordinated tranches are paid last. These tranches are the highest risk because they are the last to receive payments and may not receive any payments if the underlying assets perform poorly. However, these tranches also have the potential for the highest returns, which is why they are attractive to investors seeking higher yields.

The waterfall model ensures that the more secure, senior investors are compensated first, which makes these securities attractive to risk-averse investors. Meanwhile, the subordinated tranches offer higher yields to investors who are willing to take on more risk, balancing the structure in a way that makes it suitable for a wider range of market participants.

The impact of the waterfall structure on financial modeling is significant. It not only determines the order of payments but also directly influences the pricing and risk assessment of each tranche. For instance, if the underlying asset pool performs poorly, it is the subordinated tranches that will absorb the losses first, protecting the senior tranches from default. This layered structure can make complex financial products more attractive to investors by ensuring a level of protection for those in higher-priority tranches.

In structured finance models, the tranche waterfall can become much more intricate, with multiple layers and varying levels of risk. Financial institutions may design these models to suit specific market conditions, investor preferences, and asset types, creating a highly flexible approach to managing and distributing risk across a pool of assets.

Financial models involving tranching are designed to redistribute risk while offering tailored opportunities for investors. By calculating yields based on tranche priority and using the waterfall structure to determine payment distribution, these models provide a flexible and effective way to create diverse investment products. Understanding how to calculate yields and how the waterfall structure works can help investors make more informed decisions when navigating complex financial instruments like CDOs or MBS.

The Advantages of Tranching

Tranching offers a range of benefits that make it an attractive tool for financial institutions and investors alike. By breaking down complex financial products into layers with different risk and return profiles, tranching provides flexibility, risk mitigation, and the ability to cater to a diverse range of investor needs. It enhances market efficiency and liquidity, making it easier for investors to buy and sell securities. Additionally, tranching can improve the overall stability of financial markets by spreading risk and aligning investments with specific financial goals.

- Risk allocation and diversification: Tranching allows risk to be spread across multiple layers, ensuring that no single investor is overly exposed to the downside risk of the underlying assets.

- Catering to different risk appetites: Tranches with varying risk profiles enable institutions to attract a wide range of investors, from conservative ones seeking stability to risk-seeking investors willing to take on more risk for higher returns.

- Enhanced liquidity: By creating tranches with different risk levels, tranching makes financial products more tradable, improving liquidity and enabling investors to easily enter or exit positions.

- Customizable risk-return profiles: Tranching allows for the creation of highly customizable investment products, enabling financial institutions to meet the specific needs of investors and market conditions.

- Attracting a broader investor base: With tranching, financial products become more appealing to different investor classes, including those with varying levels of risk tolerance and investment strategies.

- Stabilizing returns for senior investors: Senior tranches provide more stable returns, as they are the first to be paid out and thus less affected by defaults or poor performance of the underlying assets.

- Higher potential returns for subordinated investors: Subordinated tranches offer higher returns, providing an opportunity for investors to earn greater rewards in exchange for accepting increased risk.

The Risks of Tranching

Despite its many advantages, tranching comes with its own set of risks. These risks can affect both the investors and the institutions involved in creating and managing these financial products. The key risk with tranching is that the performance of the underlying asset pool can significantly impact the lower tranches, leading to losses. Additionally, the complexity of structured products with multiple tranches can lead to mispricing of risk or misunderstanding of the true exposure, making them harder to assess and manage.

- Potential for mispricing risk: If the risk associated with lower tranches is not accurately assessed, investors may be misled into underestimating their exposure, leading to unexpected losses.

- Concentration of risk in lower tranches: Subordinated tranches are highly sensitive to defaults and poor performance in the underlying asset pool. If defaults exceed expectations, the risk in these tranches can lead to significant losses.

- Complexity and opacity: The complexity of the tranche structure, particularly in multi-layered securities, can make it difficult for investors to fully understand the risks involved, leading to poor decision-making or market inefficiencies.

- Impact of economic downturns: During periods of economic stress or financial crises, the performance of underlying assets may decline, causing more defaults and disproportionately affecting the lower tranches, which are last in line for payment.

- Liquidity risk for subordinated tranches: Lower tranches may be less liquid, meaning they can be harder to sell or value accurately, especially in turbulent market conditions.

- Regulatory challenges: The complexity of tranche-based products can create difficulties for regulatory bodies trying to ensure that these products are fair and transparent, potentially leading to legal and compliance issues.

- Overexposure to systemic risk: If a large number of financial products are similarly structured with high concentrations of risk in subordinated tranches, a broad economic downturn or asset performance collapse could have a wide-reaching impact on the financial system.

Conclusion

Tranching is a powerful financial tool that makes it easier for investors to choose the level of risk and return they’re comfortable with. By breaking down large, complex financial products into smaller, more manageable tranches, it offers flexibility, helps spread risk, and makes these products accessible to a wider range of investors. Whether you’re a conservative investor looking for stability or someone willing to take on more risk for a potentially higher return, tranching allows you to pick the slice that fits your needs. It also gives financial institutions a way to structure their products in a way that meets the needs of different investor profiles, improving liquidity and making these securities easier to trade.

However, as with any financial tool, tranching isn’t without its risks. Understanding the different types of tranches and their impact on risk and reward is crucial before diving into these investments. While senior tranches offer more security, lower tranches come with higher returns and more exposure to defaults. It’s important to carefully assess how these products fit into your overall investment strategy, especially in times of economic uncertainty. By getting familiar with how tranching works, you’ll be better equipped to make smarter, more informed decisions in structured finance and beyond.

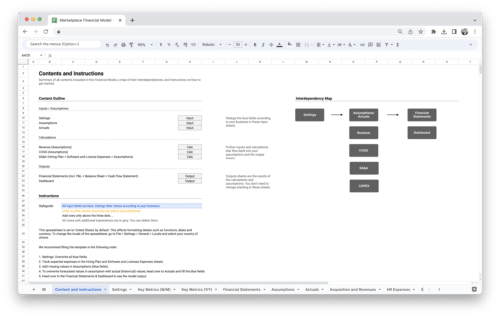

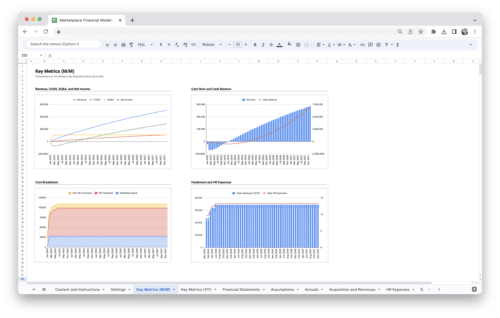

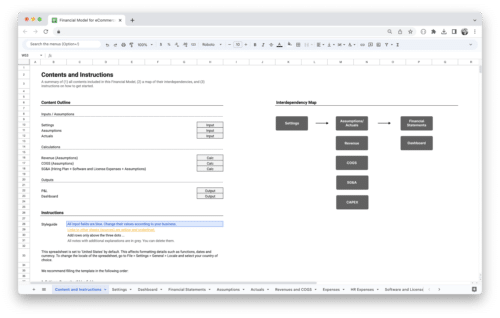

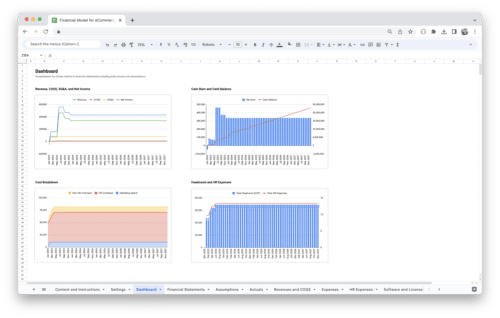

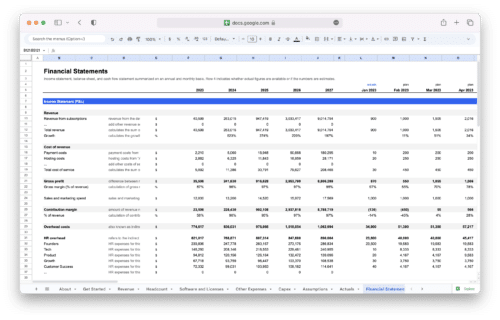

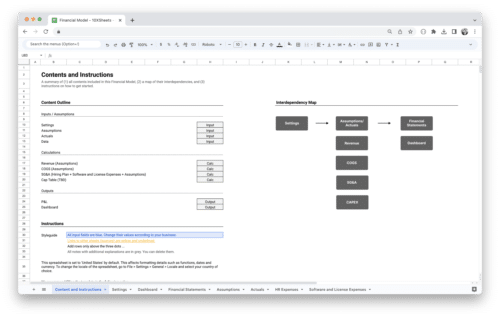

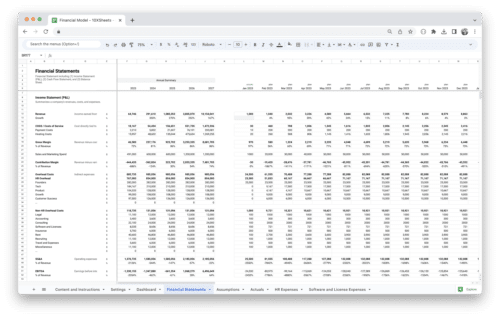

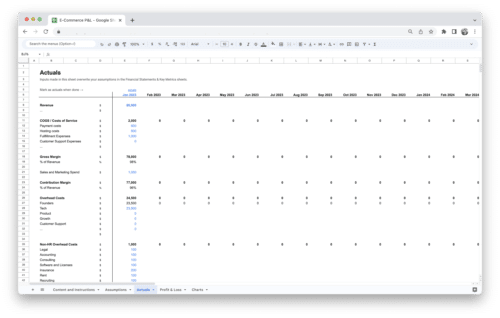

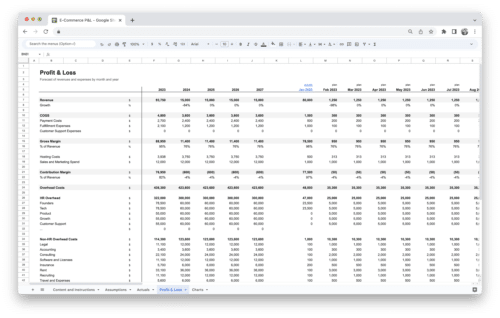

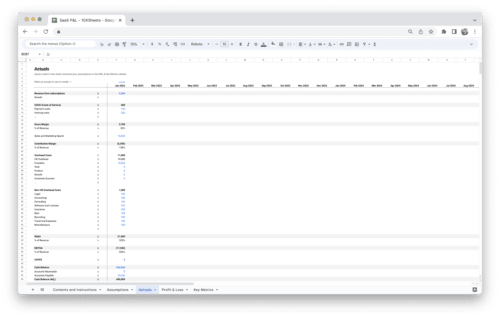

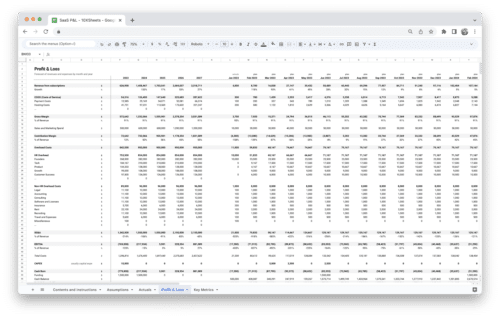

Get Started With a Prebuilt Template!

Looking to streamline your business financial modeling process with a prebuilt customizable template? Say goodbye to the hassle of building a financial model from scratch and get started right away with one of our premium templates.

- Save time with no need to create a financial model from scratch.

- Reduce errors with prebuilt formulas and calculations.

- Customize to your needs by adding/deleting sections and adjusting formulas.

- Automatically calculate key metrics for valuable insights.

- Make informed decisions about your strategy and goals with a clear picture of your business performance and financial health.